I have a million things on my mind and nothing I can do about them tonight so why not immerse myself in the scary and strange? Plus, my niece is reading 1984 for her English class and I want to be able to talk about it with her since we often have the best conversations about music, movies and books.

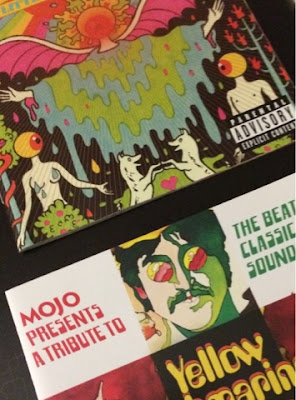

Anyway...I'd forgotten Orwellian specifics like thoughtcrime, doublespeak, Newspeak, children that frighten and report their own parents, slogans like "War Is Peace/Freedom Is Slavery/Ignorance Is Strength." The novel does still creep me out as much as I remember which is probably why I'm listening to Yellow Submarine and With A Little Help From My Friends cover albums to counter the hate of 1984's world with the love of Beatle-inspired music.

I'm also doing some background searches and I found this old New York Times article about a tv special that aired on CBS in 1983. It's not really relevant to understanding the book more, but it is kind of interesting to think back to the early 80s and wonder what the future was going to be like.

The line about having the technology of 1984, but not the intent is chilling...and when you think about how much more technology (and so many cameras, everywhere!) we have more than thirty years later, it's downright alarming.

"1984 Revisited"

(June 7, 1983)

By JOHN CORRY

IT has always been unclear whether George Orwell thought of ''1984'' as a warning, prophecy or satire, or even, as the writer Anthony Burgess says he did, as ''a kind of game, a horrible game.'' On the other hand, it may not matter. Orwell's novel resonates in the popular culture, anyway. The title is a synonym for the death of privacy, the end of freedom. Orwellian, as an adjective, means dehumanizing and bureaucratic. How close are we now to an Orwellian world? Walter Cronkite looks for an answer in ''1984 Revisited,'' on CBS-TV at 8 o'clock tonight.

Mr. Cronkite is an inspired choice for this. For years he has been a familiar presence, sharing and interpreting for us the great events of our time. Moreover, he has been a reassuring, trustworthy presence. If Mr. Cronkite has looked worried, we have worried. If he has seemed pleased, we have been pleased. In a benign way, he has been very much like Orwell's Big Brother, a constant electronic visitor, with perhaps the most recognized face in the country.

Therefore, viewers will note that Mr. Cronkite seems concerned, but not overly worried, that Orwell's nightmare vision of dictatorship will soon overtake us. Judging by the evidence on ''1984 Revisited,'' Mr. Cronkite's reaction is probably correct. The technology for dictatorship may exist in America; the will to apply the technology hasn't yet surfaced. Vigilance, Mr. Cronkite suggests, will protect our future.

Other nations are not so fortunate. Orwell's Oceania used torture to enforce policy. A spokesman for Amnesty International says in an interview that his organization has acted on cases of torture in 60 countries. Oceania, meanwhile, rewrote history, creating unpersons. A slogan of Big Brother's party said: ''Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.''

Similarly, the Soviet Union has rewritten its history, making unpersons, for example, of Trotsky and Lavrenti Beria. Revisionism goes on in democratic countries, too. Japanese high-school textbooks, Mr. Cronkite notes, omit the 1937 massacre known as the ''Rape of Nanking'' and dismiss the invasion of Manchuria as an ''incident.''

In the United States, the author Frances Fitzgerald says in an interview, textbooks have tried to ignore the Vietnam War. This isn't pursued on ''1984 Revisited,'' however, presumably because there is a great gap between the systematic, enforced rewriting of history and the half-hearted rewriting of publishers who pander to the whims of school boards. Indeed, much of ''1984 Revisited'' deals not so much with the threat to our civil liberties as the appearance of the threat, not so much with what is as what could be.

Certainly it is true, as ''1984 Revisited'' says, that electronic surveillance grows, that computers run large parts of our society, and that chemicals can alter our minds in frightening ways. These are potential threats to our liberties, although the larger threat may lie in how easily they have been allowed to enter our lives. One wishes that ''1984 Revisited'' had examined the complaisance, the eagerness even, with which we embrace the new technologies.

Orwell, in his frequent paeans to the common sense of the ordinary British citizen, admired a kind of crankiness that would not have tolerated these intrusions. Whatever happened to the crankiness? In a telling aside, Mr. Cronkite points to eight boxes, shoebox sized, and says they hold all of Orwell's personal papers - letters, memos, a checkbook, a press card. Orwell was not a man to leave his private life lying about. But if he were living in America today, as Mr. Cronkite notes, the computer printouts on his life, from Government and private sources, would fill a room.

''And such printouts,'' Mr. Cronkite says, ''put us a lot closer to Orwell's vision of a world without privacy.'' They do indeed; they also contribute to a kind of homogenization of America, the submerging of personal identities - the essence of Orwell's Oceania. Television, with its enormous power to both define and promulgate the culture, helps in the homogenization, too. ''1984 Revisited'' is serious and responsible in its exploration of an Orwellian world. One might wish it had pushed its exploration further.

No comments:

Post a Comment